- The Nightclub Artiste

- Risto's Riff

- Them Call Themselves Old Punks

- Ugly Flower Pretty Vase

- City Wrecker

- Prairie Boy

- The Queen Of Both Darkness And Light

January, 2014. I am one hour north of where I live in Helsinki, in a small town called Hameenlinna. I see little yellow wells of urine in a snowbank and I think, ‘Those aren’t ours, not yet,’ and ascend the front steps of what must have once been someone’s home. We will live here for four days. The floors are such that we leave our boots laced. The bathroom has no toilet paper. There is still food in the fridge from the band that was here last, and it will still be there when we leave. I am here with Siinai, the band with whom I sometimes make songs as Moonface. Together we are simply called Moonface & Siinai. We will record the music in the next room, which is already cramped with instrument cases, and the amps will go in the hallway and kitchen to avoid bleed. Okay. In the live room I unpack my cables and try to remember how to set up my station. I see an old yellow organ I can use. Why not? The engineering room is nicer; it’s warmer than the rest and there is carpet in here for our toes. Eetu and Jaarno–our friends and engineers–will sit here patiently and professionally and capture whatever noises we produce next door. They are like butterfly hunters with their nets and we will toss them moths and horseflies. The next day Eetu walks in from the other room where he’s been trying to properly tune my bad old guitar and says, “It’s a piece of shit, you know,” and everyone laughs because we don’t really care. A few of us are drunk and spend a lot of time on the porch smoking and talking, debating how the songs should be played, but then back in the live room we laugh at how we can’t remember our own parts, our own decisions, our own taste in music. Markus drums himself into a trance. Matti wants everything louder, weirder. He puts his bass on the floor and squats down to twist some knob on the pedals I have no interest in understanding. Risto is sober this month (Finns do this sometimes after the holidays), he focuses on his guitar, his parts, the task at hand. Sometimes I think he is fed up with our drunken antics. Saku is his usual self: calm, sweet, reasonable; his synth sounds are clean.

We sleep in the basement, where we move boxes and mattresses around to make space. We play pool on the ramshackle table; there is no chalk for the busted cues. We turn up the heaters, zip our sleeping bags up to the top, pass out. On the second day after more recording we go to the local community centre for a sauna and a shower. Here I am, paying my four euros to the woman in the glass booth–oh wait, I need a towel–five euros. Here I am, naked with the Finns again. Here I am, fresh and red-faced from the shower. Back to the studio. At night we eat pizzas and salads in a nearby restaurant. The next day I show them a new song they haven’t heard yet. We whip it up quickly, put it to tape and call it “New Song” for the time being, and in the end it becomes the album closer. Beside the front porch hundreds of cigarette butts are strewn over the snow. They are so layered and dense that if I stare long enough I can see faces emerging from the filth.

On the last morning I take a photo of Siinai in the kitchen, and they are all eating bananas, and I post the photo online. This is something I rarely do. I am not a photographer, nor do I wish to be, as you will learn in track two.

January 2015. I am standing in my bright, spacious bedroom, in a big old dirty house, in the small town on Vancouver Island in which I live. Against the north wall is a low set of shelves. I am proud of these shelves because I built them myself–donned the old work gloves and sorted through a pile of planks in the yard that had once been a fence, sawed them to size by hand, sanded them smooth, erected them sturdily, painted them white. I am no carpenter, but these are nice shelves. Yes, I am proud of these shelves. But upon these shelves, on the very bottom shelf in fact, is an external hard drive. It’s a LaCie–a flat rectangle of silver aluminum wrapped with a thick lip of orange rubber. I took this hard drive with me from Finland when I moved last summer, because it contains all the music I recorded with Siinai, now already a year ago. But the music is still unedited, which in my mind means just a pile of notes sitting in there like loose jigsaw puzzle pieces. And the words have not been sung, because even now, not all the words have been written. The idea was that I would finish the album in Canada, but the songs still sit inside that hard drive on the shelf, unedited, unwritten, unsung. No, I am not proud of my LaCie hard drive, with its showy orange trim, snootily perched on my shelves like it fuckin’ owns the place. And as I stand here alone in my spacious bedroom I hear it whisper to me in harsh bursts, like a jackknife along the flint: “You hack. You poseur. You silly fraud! Thought yourself a songwriter? Where are the words now, Sylvia? Your friends are waiting. Oh, sorry, was that your banana that Cohen is holding? I guess he took it while you were listening to Philip Glass in reverie. Oh, sorry, was that your head that Cobain lost? And now, ladies and germs: Here Come The Luke Warm Jets! You thought you’d tricked everyone, didn’t you, but now you have nothing to say. Because you have no heart. Because you have have no soul. You’re just a zombie in a top hat, isn’t that right?” I walk over to the hard drive on the shelves and pick it up and mutter something into the air.

April 2015. I am singing in a friend’s studio, not far from my house, recording the lyrics I have finally finished. The music has been edited, and sometimes I find it has a groovy, classic feel to it that I hadn’t expected. Tonight I am alone in the studio. There is a bison head mounted on the wall, so I sing to the bison head. I have turned down the lights as far they can go and I am drinking whisky, perhaps too much, as the bison head seems unimpressed. The next day I listen back to the multiple takes and hear myself bumbling and mumbling around the room between phrases. I hear the whisky in my throat. I think: Doesn’t matter; there is usable stuff in here. And I slip my silver and orange hard drive into my inside jacket pocket and skulk back down into the editing cellar of my mind.

A week or so later I am in this studio again, this time with friends who have kindly agreed to sing the backup vocals. They humor my melodies and turns of phrase like they are tasting food made by a child. They are patient and accepting and open. They are kind, yes, they are good sports, and so they have a drink as well and they get into it. They sing, “What you did in front of everyone… la la la … in the middle of the nightclub… la la la.” And from the control room I yell into the talkback microphone, straight onto their eardrums via the headphones on their unsuspecting heads, this asinine suggestion: “For inspiration just think of Danny DeVito dancing in a white tuxedo in a cave!” And they say: WTF? And I say: “You know, from the movie The Jewel of the Nile? The soundtrack has a Billy Ocean song and there’s a music video where he and Danny Devito are singing that song and dancing in white tuxedos, in a cave, in the jungle! And there’s this great mid-tempo groove… so… just channel DeVito dancing in a white tuxedo to find the feeling!” And afterwards I show them the video on my phone, and we see then that I was wrong about the jungle and the cave – they are in fact just on an ordinary stage (why, memory, why a cave?) – and besides Ocean and Devito there is also an entire band, and Michael Douglas and Kathleen Turner flanking Devito. But I am right about the white tuxedo; about groovy DeVito and the groove. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-n3sUWR4FV4

November 2015. I am lying on the couch at Breakglass Studios in Montreal. After a summer and fall of sporadic tweaking, fussing, and procrastinating, I am finally relinquishing control over these tunes. Jace is giving it his sweet mix, and I have flown out to join him for the last couple days of the session. Why not? So now I am half asleep, marvelling at how fast he is with his Protools-mouse-hand, and I hear some three-second snippet of a vocal or drum part he’s working on, and I ask him if he thinks we should change the blah blah blah of the blah blah, and without turning around he says, “No, leave it. It’s good,” so then I say, “Oh, okay,” and go back to daydreaming about my dog. This is the basic structure of our working relationship, and so far it’s working out. At some point he tells me he really likes the ending of City Wrecker, and says that I should name the album after that song, and I laugh and tell him that my last EP is already called City Wrecker, and that particular song on this LP is like a full-band cover of the solo version. And when I say this I can see in his face that he’s never heard the solo version; doesn’t even know it exists. And this warms my heart, because it shows me: We are friends with another before we are fans of one another, and that’s important. Later, we eat smoked oysters on crackers in his kitchen and watch Canadian news on his iphone.

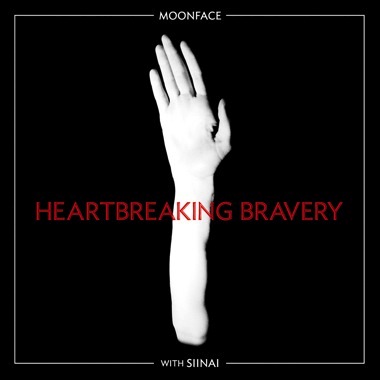

February 2016. I am at my desk and I have a head-cold while I am writing this. I am drinking a thick tea of boiled lemon wedges and ginger with honey. It’s helping. Looking back, I see it took a long time to realize this LP, and I didn’t even tell you about the jam sessions on the outskirts of Helsinki that preceded the recording session, the bleak winter darkness that forced us indoors to write the music in the first place. But sometimes things take longer than you expect. I am slowly learning to expect nothing, and then be pleasantly surprised whenever something actually unfolds all the way out, like an arm, to pull me up. But I am here now fighting this cold with this LP finally finished, and there is some bittersweetness in my heart, because I honestly don’t know if I’ll ever record with those Siinai boys again. With our first LP together, Heartbreaking Bravery, we threw some kind of stone into the water, and now are each riding a different part of the same ripple, spreading outward, so that even though we are connected we can only get further away from one another. I see that now. And I am telling you now: I called this thing My Best Human Face not only because that’s one of my favorite lines on the album, but because I sometimes don’t know who I am, or if I’m as kind and generous and happy as other people.The title speaks to the vague theme of identity-confusion that is loosely woven into the songs – a reoccurring theme I recognized only after the writing was done. It’s a confusion which I think exists for most of us, sure, but that doesn’t mean it has to be the campfire in the middle of our circle; we don’t have to stare into the flames. It’s simply not that important. At end of it all, these are good-time songs, meant to inspire good times in the listener. They were made joyously, with a stubborn love of music at their centre. And while some of the content might be dark or sad, the memories of making these songs brings only gladness and gratitude, and it’s their construction, not deconstruction, that I want to celebrate now.