- Worlds Unknown

- Evil Twin

- Long Weekend

- Barfly

- Windows on the World

- Walk in an Absent Mind

- Don’t Look Down

- Shut In

- Out of Touch

- Dream

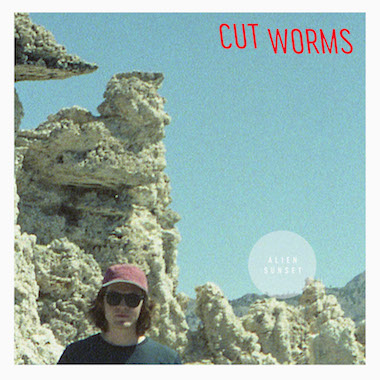

Cut Worms — Transmitter

“The cut worm forgives the plow.”

William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

Below the surface, worms are at work—soft and unseen, renewing in silence. Like organs of the earth, essential yet overlooked, their existence reminds us that survival is never without violence: the plow cuts, harvests kill, life feeds on life. This image has lingered with Max Clarke for years, guiding his fascination with the space between destruction and growth, innocence and experience—a duality that finds its fullest expression yet on Transmitter, his fourth full-length as Cut Worms.

Produced by Jeff Tweedy at Wilco’s Loft studio, Transmitter marks a deepening of Clarke’s abilities and the convergence of two artists whose work searches for grace amid dislocation. Together, they conjure the ecstatic spirits of power pop and alt rock, expanding Cut Worms’ vintage palette while reaffirming his gift for timeless songwriting. Clarke turns his gaze into the private worlds we all inhabit but rarely share, and out toward a country suspended between illusion and collapse. These are places shaped by the myth of self-reliance, where people sold the idea of connection through technology have been reduced to quiet transmitters—data points bought and sold, manipulated and measured, their lives distorted through the very networks meant to unite them.

“I don’t really make concept albums,” Clarke says, “but inevitably you have to put all the things in one container. In Carl Sagan’s novel Contact, Earth receives communication from a distant star system, and it turns out to be an old TV broadcast sent back with an encrypted message. I liked the idea that songs could work the same way—like beams of light carrying a message you just have to tune in to feel.” Now several albums into his career, Clarke stands fully in command of his craft, resonating at his own frequency. What began as a passion for bygone pop has matured into a study of endurance itself, confirming him as a singer-songwriter of lasting depth—one whose vision stands comfortably alongside figures like Tweedy, who’ve turned persistence into art.

The first signs of Transmitter came when Cut Worms were on the road supporting Wilco in the summer of 2024. At the end of the tour, Tweedy invited the band to record at the storied Loft in Chicago, and plans were soon made to commence that fall. The opportunity was a homecoming of sorts for Clarke—the Windy City is where he attended art school, played in formative bands, and began recording his Cut Worms Soft Boiled Demos. Sharing the stage with Wilco was already a dream, but to return to Chicago with a new batch of songs and the chance to work alongside Tweedy felt like a circle closing and a new chapter beginning.

In the Loft’s warm clutter of guitars, amplifiers, and books, Clarke and Tweedy quickly found common musical ground and a shared instinct for songs that hold complexity. Unlike earlier records defined by Clarke’s own guitar style and knack for arrangements, Transmitter took shape as a dialogue. While his voice and writing formed the framework, Tweedy’s guitar and bass lines sketched the rooms the songs inhabit, raising walls around them without ever sealing them off. “Jeff instinctively understood who the narrator was and what the story was about in each instance, without me ever needing to say it outright,” says Clarke. Tweedy’s presence as a producer revealed itself not in heavy-handed choices but in how he colored spaces and continually offered new textures. His veteran knowledge and exceptional playing gave Clarke the confidence to let the songs flow more freely. Between them, their like-minded sensibilities bridged a generational gap to create something more nuanced than either might have made alone.

If previous Cut Worms releases were steeped in Brill Building decadence and madcap Americana, the sound on Transmitter feels darker, richer, more saturated with the anxiety of contemporary living. Hope seems fragile here, but the songs still dream. The record opens with “Worlds Unknown,” its surging guitar lines immediately announcing a rawer energy; similarly, “Long Weekend” accelerates time itself, carrying the melodic urgency of Big Star or Dwight Twilley. “Evil Twin” wrestles with bitter disappointment, its talky guitars recalling the jangling heartache of The Replacements and The Go-Betweens, and “Windows on the World” leans toward the sun of the future with a melancholy that drifts somewhere between Elliott Smith and Miracle Legion.

Despite Transmitter’s heavier edge, the songs just as often drift into quieter realms of reflection. “Walk in an Absent Mind” confronts the awkward stagnation of life’s cycles (“drinking straight from an hourglass”), the impulse to escape and the recognition that we might need others after all. “Barfly” sits in that same restless space, capturing the weary struggle to connect with others until a spark finally catches, while “Shut In” embraces the comfort—and the peril—of retreating from the world. “Each song is like an SOS put out to anyone who might be listening,” Clarke explains. In tracing these signals, he has drawn a map of the human condition and found poetry in the missed turns, the circling back, and the small gestures and fleeting encounters along the way.

Threaded through these portraits is the awareness that time is always passing. Clarke writes of the American Dream flickering on a TV set, revealing how flimsy our visions of tomorrow can be—burned on the screen, but never quite matching the life we thought we’d discover. Still, the album occasionally glimmers with optimism—whether it’s the promise of a chance encounter or the light of dawn forming in a lover’s eyes, we feel that the horizon is visible, even if always receding. Clarke muses, “Amid all the darkness and existential dread, the human spirit’s prevailing conviction is that despite everything, somehow it will all work out, because what other choice is there?” Closing track “Dream” brings us back to a familiar plane: Clarke alone at the piano, tender and unresolved, pondering the fate of dreams and the risk of falling short or getting lost en route.

Transmitter finds Clarke in full stride, writing with the conviction of someone who’s made peace with uncertainty. These songs reckon with the cost of comfort and return to the idea that beauty, connection, and love are not luxuries but necessities for survival. Like Blake, Clarke is drawn to paradox—the friction between intimacy and escape, faith and doubt, shadow and light. His forgiveness, like the cut worm’s, comes through transference: the act of releasing something fragile into the noise and trusting it might still be felt. Can we stop the plow? Maybe not. Yet Clarke urges, “whatever you put out into the world will find resonance. Everyone is emitting signals and vibrations, so be mindful of what you’re sending.” The truth may not always be understood, but it can be felt. Clarke’s music resides in that current—searching without pretending to have the answer, a songwriter no longer looking for his voice but testing how far it can reach. There is something for us in that search too: a reminder that even in fractured times, we might still find compassion, empathy, and the courage to keep going.